“Your team walks into the chamber. On the wall to your right is a board, listing a number of tasks that you need to complete. A clock on the far wall begins counting down. You have two weeks. What do you do?”

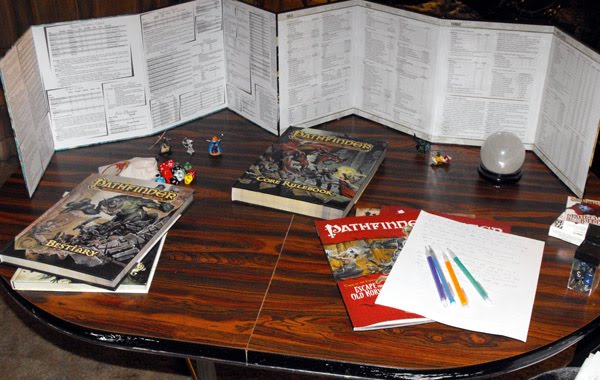

Long before I became a Scrum Master, I was master of another sort — a Game Master (or GM). The role goes by many names, depending on the game. To some it is Dungeon Master, to others it is Story Teller, and to still others, it is Referee.

The GM was the person tasked with learning the rules of the game. They set up the environment for the players. Described the setting or scenario. They controlled what outside forces were allowed access to the players. And they acted as referee in disputes both within the party, and from the outside. Ultimately, the GM is responsible for helping the team achieve their goals.

Sound familiar?

It’s possible that part of the reason that I took so readily to the idea of being a Scrum Master is because I had already spent so much time behind the GM screen. There are definite parallels between the roles. Although both are at the center of the action, and both are intimately aware of the situation and the status of forces within and without the group, neither is able to take over and drive the outcome. In both situations, jumping in and enforcing outcomes would be met by resistance, and ultimately result in a less-than-optimal outcome.

In a roleplaying game, the players take on the personas of the heroes of the tale. They are presented with a series of challenges, and must react to each of them in turn, employing their abilities and talents to affect the outcome of the game. Most of the challenges require skills from more than one party member in order to complete them successfully. Each challenge is a puzzle that the team needs to work together to find a solution for.

In order for the players in a roleplaying game to truly enjoy themselves, you have to give them the freedom to choose their own actions. If you attempt to script their actions, they are no longer calling the shots – they become passengers in a story that you write for them. You take away autonomy, and you lose the collaborative nature of the roleplaying experience.

One of the things that keeps the players of one of these games coming back for more, is the chance for their characters to gain skills and new abilities as the game progresses. With every passing challenge, they gain levels of skill. Every encounter becomes a learning experience. In later challenges, they apply things they learned in previous sessions – learning to avoid certain pitfalls that they have seen in the past.

Roleplaying games can be very short, lasting only a single session. But they can also string several related adventures together to form a campaign. For a campaign to succeed, the GM needs to provide something larger than the short-term challenges and victories of the individual sessions. The GM must provide a long-term challenge. A vision of something larger than the characters, that they will strive to get closer to with each passing session.

The same challenges face Scrum Masters while starting out with a new team. The Scrum Master knows the rules, and sets up an environment that should allow the players to face their challenges. To identify the tasks necessary to complete each story. To respond to surprises, and gain levels of understanding. To work together to achieve their goals.

There was a point in almost every game that I longed for. It was the moment when the players forgot they were playing a game. When they reacted to the scenarios as if they were their characters. They were caught up in the moment, and the story flowed more through their actions and reactions than any input I provided. I have experienced the same flow in a scrum team room, when something clicked and every member of the cross-functional team was working together to achieve their sprint goal. It is an unmistakable energy, and one of the few rewards that a Scrum Master (or a GM) can enjoy – not because they did it – but because they created an environment for the team in which they were driven by a sense of autonomy, mastery and purpose to achieve great things.

It makes it all worthwhile.