Voice on phone: “I need an Agile Coach.”

Me: “Great! Tell me about where you are in your agile journey.”

Voice on Phone: “I’m at the part where I need a coach.”

Me: “Okay. What kind of coach?”

Voice on Phone: “…”

This happens a lot these days. The understanding that there is more than one type of coach has not sunk into the corporate psyche yet. Perhaps because in the greater scheme of the 20+ year arc of agility, we have only recently come to the realization ourselves.

Let’s examine a couple sources of “coaching”…

The Scrum Master as Coach

There was a much simpler time, when all we had was single teams and coaching was performed by the Scrum Master. If you wanted to be a Scrum Master, it helped to be certified (or so we assumed). Later, it became obvious that a certificate alone proved nothing more than you had survived a two-day class. You theoretically knew what Scrum did. It took a painstaking process of trial and error for most fledgling Scrum Masters to reach true maturity.

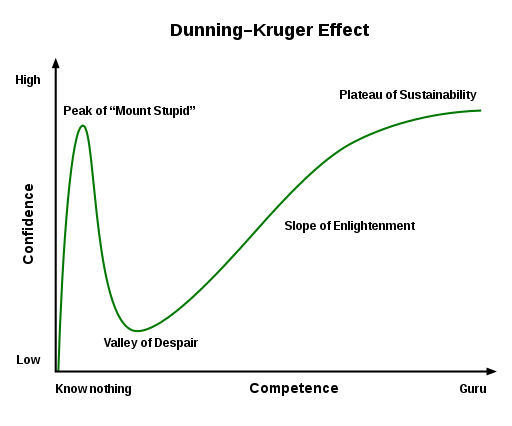

This is a great example of the Dunning-Kruger Effect. When you first learn a thing, you know all that you know about a thing, and have no idea of how much else there is to learn. It looks a little like this:

I won’t belabor the point. A lot has changed since those days, but one thing remains the same: No amount of training can take the place of the experience of doing. And no amount of doing will be truly effective until you understand the “why” behind the doing.

In those days, every freshly certified Scrum Master came out of their two-day class with a level of confidence that frankly was born of ignorance. Well-meaning, innocently contrived, but ignorance, nonetheless. The lucky ones (and I count myself among them) managed to have their challenges unveiled in small, manageable chunks and had time to work them out. But every Scrum Master seemed destined to earn their expertise in the same way. Through trial and error.

Some people were better equipped to handle the abstract nature of the agile learning curve. Some people were ‘wired for agile’ – which absolutely gave them a leg up in “leading” their teams to success. (By “leading”, I mean they embraced their role as enabler and supporter. The teams’ successes were their own doing.)

The Project Manager as Scrum Master

Then there were those Scrum Masters who arose from the old guard – who embraced direction and enforcement. They were very much wired for the deterministic/directorial role of a Project Manager, and dismissed as unimportant the servant leader aspect of the Scrum Master role. When coaching fell into the lap of a recovering Project Manager, the teams didn’t learn the ‘why’ of agility, and instead focused on execution of the process (the ‘what’ of the agile frameworks).

It wasn’t so much coaching, as it was check-listing. And believe me, they were excellent at checking boxes! Predetermined, uniformly sized boxes. The philosophical underpinnings of agility were de-emphasized. In other words, more “doing Agile” and less “being agile”.

This was a critical point for agile adoption at large, and it was a major point of failure. Many organizations were taking their most trusted executors of delivery and handing them a job (they thought) the individuals would continue to thrive in: namely, being responsible for all aspects of project delivery.

So why didn’t this work out so well?

One of the biggest disconnects here is that Project Managers assign work, collect status, manage risk, and report status. In agile, all of those activities are owned by the people who do the work and are largely built into the framework. Instead, we had these Project Managers, sitting at the head of the Scrum Room table (as they do), feeling responsible for the Scrum Team’s success, feeling accountable for their failures, and feeling justified in stacking the deck toward success by hanging onto the oversight and reporting of the work.

As a result, we had all of these beginner teams being paired with beginner Scrum Masters, who were not the experts in agility we needed them to be. The Teams never grew to maturity. They never embraced autonomy. They simply waited for the inevitable orders to be handed down. The term “agile” became a euphemism for “micro-management”. Rather than feeling empowered, the teams experienced the exact opposite.

Coaching Within and Without

According to the Scrum Alliance, the Scrum Master is the primary coach of the team – and that is absolutely true in a world where there is one team working from one backlog answering to one product owner. A Scrum Master at this level helps their team grow in their agile maturity by learning how to work together to achieve their sprint goal. They will help identify impediments, and work with the team to find solutions so the work can continue. This is an inward-facing stance, and it’s what most Scrum Masters spend the majority of their time on — working within the team, for the team, on the team.

Occasionally, impediments will come from outside sources, and this will be the first gateway opportunity for the would-be coach to show what they’ve got. This is when the Scrum Master faces outward, beyond the team. Maybe it’s a dependency with another team. Maybe it’s a stakeholder who isn’t providing needed information in a timely manner. Maybe it’s a manager who just can’t stop assigning little one-off assignments to individual team members. Maybe it’s a director demanding to see allocation and utilization figures for all the developers on the team. This is the point that the Scrum Master needs to embrace Courage.

They may intellectually accept that they are required to protect their team, but are they prepared to do the next part? The part where they identify the source of the conflict, and if necessary, offer to educate the offending party on a more effective way of interacting? This will likely involve having an uncomfortable conversation with someone who outranks them on the corporate org chart – maybe by a lot.

Here There Be Dragons

I’ve seen it many times. The challenge arrives. It’s affecting the team in a bad way. The Team asks the Scrum Master for help. The Scrum Master sees the direction from which the challenge came, takes a deep breath, gazes into the abyss, and… turns back shaking their head. “That’s just the way we do things around here.” The impediment goes un-answered. The team learns to “just live with it”. Another coffin nail is driven into the heart of organizational agility.

To be fair, sometimes an organizational culture acts as though challenging a superior is unthinkable. For one reason or another, the Scrum Master has legitimate reasons to fear that raising such a challenge will be a career-limiting move. In their mind, retribution will surely follow. If not today, then at the end of the year when annual reviews come around. Hell, it seems, hath no fury like an executive rebuked (or something like that).

To be equally fair, the leader in question may not be the petty ogre the Scrum Master fears. They may be perfectly willing to listen, to learn, to change. But odds are, that somewhere in that Scrum Master’s past, they either faced it themselves, or heard a story of someone else who took the risk and paid a hefty price. And that’s sad.

Regardless of the source, real or imagined, the urge to step away an let the problem live on, is the source of many of the ills I’ve seen when beginning an engagement with a new client.

The Agile Coach as an Independent Entity

And hence, the Agile Coach as an independent role came into being. The Agile Coach is an individual who comes from outside the normal chain of command in which a team operates.

Often the coach is a consultant (or at least a contractor). They ride into town in response to a cry for help. They diagnose the problems, and help the townsfolk learn how to stand up and hold their own against the things that are plaguing them. And then they leave, riding off into the sunset having equipped the townsfolk with the skills they need to continue their agile journey on their own.

So going back to that external impediment that resides in the corner of the organization where the internal angels fear to tread… this is where the external coach has an advantage. The external coach comes from outside the corporate structure. They are not beholden to the status quo. They don’t know that they’re “supposed to” be afraid of asking hard questions. And in that ignorance, they are blessed with the opportunity to be effective! (And yes, they will occasionally fall prey to upsetting the wrong apple-cart, and getting shown the door as a result.) An experienced coach has probably been fired at least once for trying to do the right thing. A skilled coach has adapted their approach to minimize that potential outcome (usually in the form of a coaching agreement).

I have heard it argued that if you’re not willing to risk your job, you aren’t really being an effective coach. And obviously, the intent of the external coach is to be a temporary factor anyway. They already plan to go – it’s just a matter of when they leave. (See Black Hat / White Hat for a little more on this topic.)

Who Should Coach?

So, setting aside for the moment that all Scrum Masters are a form of coach, let’s focus on this concept of the stand-alone coach role. That is, the person wielding the title of “Agile Coach”. More and more, I see organizations stepping away from the contractor coach, and building this capability in-house. From a financial standpoint, this makes sense – especially if you intend to keep the coaches around for an extended period of time.

Some organizations will hire someone who is already an experienced coach. Others will try to find someone in-house to fill the role. That can work – absolutely that can work. But it can also backfire. It’s similar to the idea of taking a project manager and expecting them to be wired for the Scrum Master role. The potential challenge here, is that someone from inside the organization, is already familiar with the established culture. They know the corporate hierarchy, and their place in it. Further, they have become accustomed to ignoring the elephant in the room. That big, ugly elephant that is crushing your organization’s ability to move forward – the elephant that nobody speaks of. This internal coach will likely remain silent about it, because that’s just the way we do things around here.

I suppose it depends on intent. If someone is looking to be an agile coach simply to have a little more authority over telling teams how to do their work — to essentially be a bigger, badder Scrum Master — then I would argue they’re not really coaching.

If on the other hand, someone sees the team as a part of a larger ecosystem, and can not only see the team’s place in that maelstrom, but how other teams, departments, individuals, policies and practices are impacting the ability of organization to function. If they are adept at seeing the trouble-spots (even if they don’t know the answer yet) and have the curiosity to seek a root cause and the ability to bring others along with them on that journey… those folks are likely capable of effective coaching.

I have been at many organizations, and within each one, found individuals who I recognize as having that spark. I always try to encourage those folks to expand their horizons. I will have frequent mentoring sessions with them. I will engage them in discussions about motivation and drivers. To see if they can discern the root problems beyond the symptoms. Sometimes they can. Often their vision is clouded by being too deeply mired in the system.

Organizational Antibodies

Many corporations function like a living organism. There are distinct structures and roles within the organization. They not only exist to preserve the life of the organization, but to also preserve their own function within the organism. They are always on the lookout for threats to their health or station. It’s a natural byproduct of the cutthroat nature of corporate America.

I recall one time, when I was a full-time, internal employee, trying to advise my superiors about ways to support agile teams and how approachs within our organization would have to change. At one point in the conversation, one of the leaders asked, “We’re trying to be Agile now, Mike, you’re the agile expert, what does that mean we would do in this instance?” And I answered him. And he looked me dead in the eye and said, “We’re not going to do that.” And I was thanked for my input and sent back to my day job. The struggle to be recognized outside of your corporate “role designation” is real.

Now, fast forward a few years and I’m an external coach for another company, sitting in a near-perfect copy of that other meeting. Same ranks. Same questions. They turn to me and ask, “We’re trying to be Agile now. Mike, you’re the agile expert, what does that mean we should do in this instance?” And I answered him (the same way I’d answered before). And he looked me dead in the eye, nodded, and said “Okay!” And they did it.

The External Coach as Trusted Advisor

The difference? A paid opinion over a paid role? Perhaps? It wasn’t that the information in the room was any different. I honestly think it was me and my role. An external, paid consultant, recognized as being a trusted advisor, versus being one of their own employees, who by virtue of rank, was not allowed to render an opinion.

I’m not saying it’s every organization. But I’ve seen more than a few of them do it. I’ve even heard them say things like, “That person is JUST a B.A.”, we’re not giving them that kind of authority”, or “That’s my job to make those decisions. Not yours.” It seemed more like they were protecting turf and status, than seeking solutions to problems.

So that external coach. By virtue of the fact that they are being paid for their opinion and recognized as having expertise in the transformation space. Bolstered by their ability to see the things that others fear to recognize. Are able to transcend the chain-of-command and enable the organization to change. To teach. To mentor. To guide. To build capability.

And then to move on and do it again somewhere else.

Personally, that’s why I do this. I love being that guy.